Thinking in MapReduce

This is the blog form of the Thinking in MapReduce talk at StampedeCon 2013. I’ve linked to existing resources for some items discussed in the talk, but the structure and major points are here.

We programmers have had it pretty good over the years. In almost all cases, hardware scaled up faster than data size and complexity. Unfortunately, this is changing for many of us. Moore’s Law has taken on a new direction; we gain power with parallel processing rather than faster clock cycles. More importantly, the volume of data we need to work with has grown exponentially.

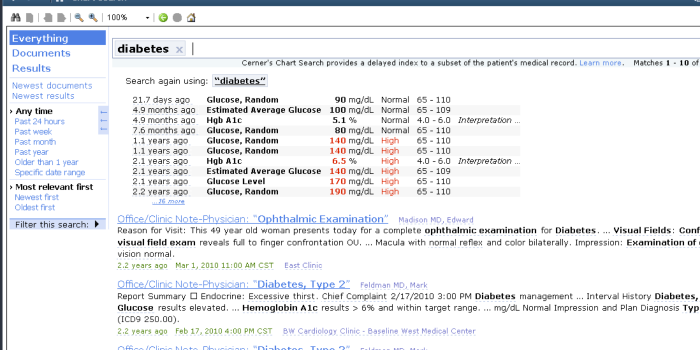

Tackling this problem is tremendously important in healthcare. At the most basic level, healthcare data is too often fragmented and incomplete: an individual’s medical data is spread across multiple systems for different venues of care. Such fragmentation means no one has the complete picture of a person’s health and that means decisions are made with incomplete information. One thing we’re doing at Cerner is securely bringing together this information to enable a number of improvements, ranging from better-informed decisions to understanding and improving the health of entire populations of people. This is only possible with data at huge scale.

This is also opening new opportunities; Peter Norvig shows in the Unreasonable Effectiveness of Data how simple models over many data points can perform better than complex models with fewer points. Our challenge is to apply this to some of the most complicated and most important data sets that exist.

New problems and new solutions

Our first thought may be to tackle such problems using the proven, successful strategy of relational databases. This has lots of advantages, especially the ACID semantics that are easy to reason about and make strong guarantees about correctness. The downside is such guarantees require strong coordination between machines involved and in many cases the cost of that coordination grows as the square of data size. Such models should be used whenever they can, but to reason about huge data sets holistically means we have to consider different tradeoffs.

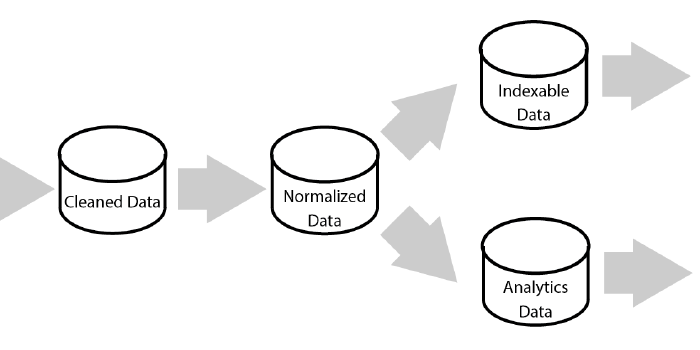

So we need new approaches for these problems. Some are clear upfront: as data becomes too large to scale up on single machines, we must scale out across many. Going further, we reach a point where we have too much data to move across a network – so rather than moving data to our computation, we must move computation to data.

In fact, these simple assertions form the foundation of MapReduce: we move computation to data by running map functions across individual records without moving them over the network and merge and combine, or reduce, the output of those functions into a meaningful result. Word count is the prototypical example of this pattern in action. MapReduce implementations as offered by Hadoop actually offer a bit more than this, with the following phases:

-

Map – transform or filter individual input records

-

Combine – optional partial merge of map outputs in the mapping process, usually for efficiency

-

Shuffle and Sort – Sort the output of map operations by an arbitrary key and partition map output across reducers

-

Reduce – Process the shuffled map output in the sorted order, emitting our final result.

We have our building blocks: we can split data across many machines and apply simple functions against them. Hadoop and MapReduce support this pattern well. Now we need to answer two questions: How do we use these building blocks effectively and how do we create higher-level value on top of them?

The first step is to maximize parallelism. The most efficient MapReduce jobs shift as much work into the map phase as possible, even to the point where there is little or no data that needs to be sent across the network to the reducer. We can gauge the gains made by scaling out by applying Amdahl’s Law where the parallelism is the amount of work we can do in map tasks versus more serial reduce-side operations.

The second step is to compose our map, combine, shuffle, sort, and reduce primitives into higher-level operations. For example:

-

Join – Send distinct inputs to map tasks, and combine them with a common key in the reducers.

-

Map-Side Join – When one data set is much smaller than another, it may be more efficient to simply load it in each map task, eliminating the reduce phase overhead outright.

-

Aggregation – Summarizes big data to be easily computed.

-

Loading into external systems – The output of the above operations can be exported to dedicated tools like R to do further analysis.

Beyond that, the above operations can be composed into sophisticated process flows to take data from several complex sources, join it together, and distill it down into useful knowledge. The book MapReduce Design Patterns discusses all of these patterns and more.

Higher-Level APIs

Understanding the above patterns is important but much like how higher-level languages have grown dominant, higher-level libraries have replaced direct MapReduce jobs. At Cerner, we make extensive use of Apache Crunch for our processing infrastructure and of Apache Hive for querying data sitting in Hadoop.

Reasoning About the System

Most of development history has focused on variations on Place-Oriented Programming, where we have data in objects or database rows and we apply change by updating our data in place. Yet such a model doesn’t align with MapReduce; when dealing with mass processing of very large data sets, the complexity and inefficiency involved in individual updates becomes overwhelming. The system would become too complicated to perform or reason about. The result is a simple axiom for processing pipelines: start with the questions you want to ask and then transform the data to answer them. Re-processing huge data sets at any time is what Hadoop does best and we can leverage that to view the world as pure functions of our data, rather than trying to juggle in-place updates.

In short, the MapReduce view of the world is a holistic function of your raw data. There are techniques for processing incremental change and persisting processing steps for efficiency but these are optimizations. Start by processing all data holistically and adjust from there.

Beyond MapReduce

The paper From Databases to Dataspaces discusses a new view of integrating and leveraging data. A similar idea has entered the lexicon under the label “Data Lake” but the principles align: securely bring structured and unstructured data together and apply massive computation to it at any time for any new need. Existing systems are good at efficiently executing known query paths but require a lot of up-front work, either by creating new data models or building out infrastructure for the immediate need. Conversely, Hadoop and MapReduce allow us to ask questions about our data in parallel at massive scale without prior build.

This becomes more powerful as Hadoop becomes a more general fabric for computation. Projects like Spark can be layered on top of Hadoop to significantly improve processing time for many jobs. SQL- and search-based systems allow faster interrogation of data directly in Hadoop to a wider set of users and domain-specific data models can be quickly computed for new needs.

Ultimately, the gap between the discovery of a novel question and our ability to answer it is shrinking dramatically. The rate of innovation is increasing.