Composable MapReduce with Hadoop and Crunch

Most developers know this pattern well: we design a set of schemas to represent our data, and then work with that data via a query language. This works great in most cases, but becomes a challenge as data sets grow to an arbitrary size and complexity. Data sets can become too large to query and update with conventional means.

These challenges often arise with Hadoop, simply because Hadoop is a popular tool to tackle such data sets. It’s tempting to apply our familiar patterns: design a data model in Hadoop and query it. Unfortunately, this breaks down for a couple of reasons:

- For a large and complex data set, no single data model can efficiently handle all queries against it.

- Even if such a model could be built, it would likely get bogged down in its own complexity and competing needs of different queries.

So how do we approach this? Let’s look to an aphorism familiar to long-term users of Hadoop:

Start with the questions to be answered, then model the data to answer them.

Related sets of applications and services tend to ask related questions. Applications doing interactive search queries against a medical record can use one data model, but detecting candidates for health management programs may need another. Both cases must have completely faithful representations of the original data.

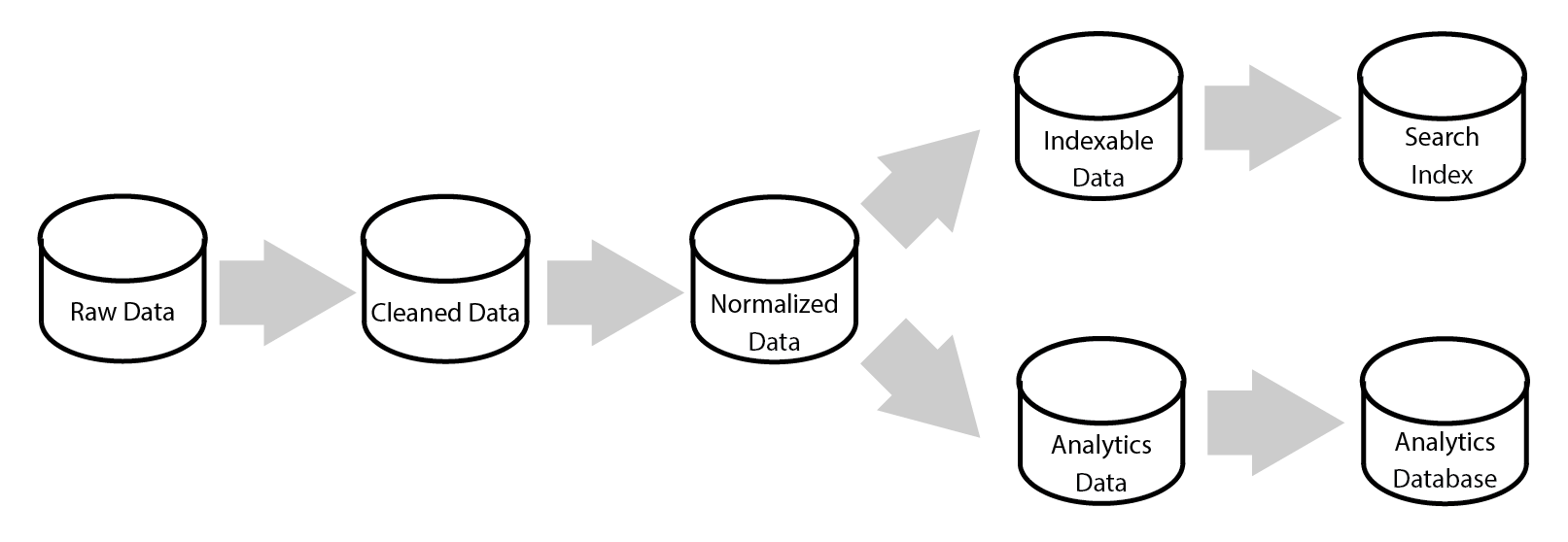

Another challenge is leveraging common processing logic between these representations: there may be initial steps of data normalization and cleaning that are common to all needs, and other steps that are useful for some cases. One strategy is for each shared piece of logic to write output to its own data store, which can then be picked up by another job. Oversimplifying, it may look like this:

Such a model can be coordinated with Hadoop-based tools like Oozie. But this model of persisting every processing stage and using them downstream has some drawbacks:

- The structure and location of each intermediate state must be externally defined, creating a barrier to easily leverage the output of one operation in another.

- Data is duplicated unnecessarily. If one of our processing steps requires intermediate data, we must persist it, even if it is used only by other processing steps. Ideally, we could just connect the processing steps without unnecessary persistence. (In some cases, Hadoop itself persists intermediate state for MapReduce jobs, but there are many useful jobs that don’t need to do so.)

- Each step must be fully processed before the next step can run. Therefore, each processing step is only as fast as its slowest component.

- Each persistent state must use a data model that can be processed efficiently in bulk. This limits our options for the data store. We must choose something MapReduce friendly, rather than optimizing for the needs of application queries.

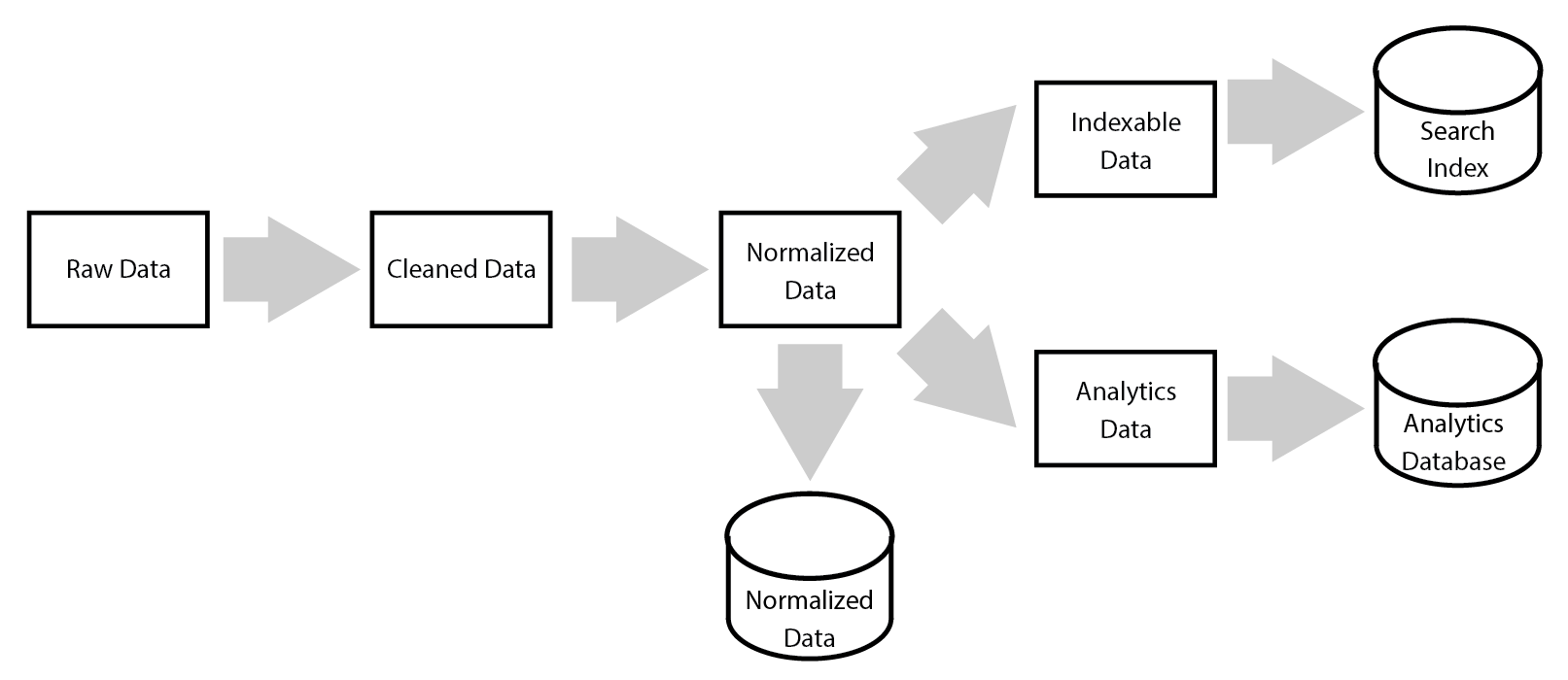

So how do we solve this? Rather than making intermediate data stores as the point of reuse, let’s reason about the system at a higher level: make abstract, distributed data collections our point of reuse for processing. A data collection is a set of data that can be persisted to an arbitrary store when it makes sense, or streamed between processing steps when no persistence is needed. One data collection can be converted to another by applying functions to it. So the above diagram may now look like this, where arrows are functions used to transform data collections:

This has several advantages:

- Processing logic becomes reusable. By writing functions that consume and produce collections of data, we can efficiently share processing code as needed.

- Data no longer needs to be stored for processing purposes. We can choose to store it when there is some other benefit.

- The data models need not account for downstream processing; they can align to the needs of apps and services.

- Processing is significantly more efficient as it can stream from one collection to another.

This model supports storing and launching processing from intermediate states, but it doesn’t require it. Processing downstream items from a raw data set will probably be a regular occurrence, but that need not be the case for other collections.

Perhaps the biggest advantage of this approach is that it makes MapReduce pipelines composable. Logic expressed as functions can be reused and chained together as necessary to solve a problem at hand. Any intermediate state can optionally be persisted, either as a cache of items expensive to process or an artifact useful to applications.

Implementation Strategy

So, how does this work? Here are the key pieces:

- All processing input comes from a source. For Cerner, the source is typically data stored in Hadoop or HBase, but other implementations are possible.

- Each source is converted into a data collection, which is described above.

- One or more functions can be run against each data collection, converting it from one form to another. We’ll discuss below how this be very efficient.

- Collections can be persisted at any point in the processing pipeline. The persisted collections could be used for external tooling, or simply as a means to cache the results of an expensive computation.

Fortunately, a newer MapReduce framework supports this pattern well: Apache Crunch, based on Google’s FlumeJava paper, represents each data set as a sort of distributed collection, and allows them to be composed together with strongly-typed functions. The output of a Crunch pipeline may be a data model easily loaded into a RDBMs system, inverted index or queried via tools like Apache Hive.

Crunch will also fuse steps in the processing pipeline whenever possible. This means we can chain our functions together, and they’ll automatically be run in the same process. This optimization is significant for many classes of jobs. And although persisting intermediate state must be done by hand today, it will likely be coming in a future version of Crunch itself.

An end to direct MapReduce jobs

We may have reached the end of direct implementation of MapReduce jobs. Tools like Cascading and Apache Crunch offer excellent higher-level libraries, and Domain-Specific Languages like Hive and Pig allow the simple creation of queries or processing logic. Here at Cerner, we tend to use Crunch for pipeline processing and Hive for ad hoc queries of data in Hadoop.

MapReduce is a powerful tool, but it may be best viewed as a building block. Composing functions across distributed collections that use MapReduce as its basis lets us reason and leverage our processing logic more effectively.