Near Real-time Processing Over Hadoop and HBase

From MapReduce to realtime

This post covers much of the Near-Realtime Processing Over HBase talk I’m giving at ApacheCon NA 2013 in blog form. It also draws from the Hadoop, HBase, and Healthcare talk from StrataConf/Hadoop World 2012.

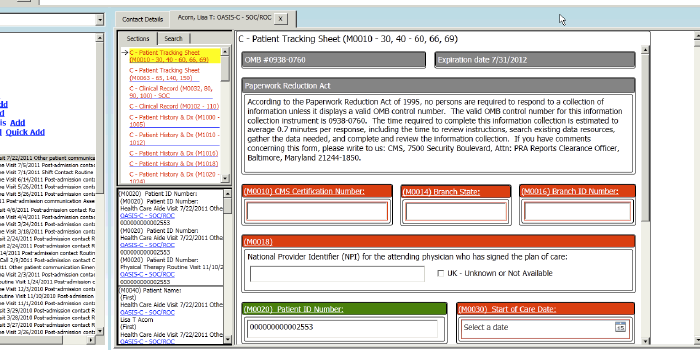

The first significant use of Hadoop at Cerner came in building search indexes for patient charts. While creation of simple search indexes is almost commoditized, we wanted a better experience based on clinical semantics. For instance, if a user searches for “heart disease” and a patient has “myocardial infarction” documented, that document should be highly ranked in the results.

Analyzing and semantically annotating can be computationally expensive, especially when building indexes that could grow into the billions. Algorithms in this space may be discussed in a future blog post, but for now we focus on creation of an infrastructure up to the computational demands. For this, Hadoop is a great fit. A search index is logically a function of a set of input data, and MapReduce allows us to apply such functions in parallel across an arbitrarily large data set.

A trend towards competing needs

The above pattern is powerful but creates a nice problem to have: people want the output of the processing – in this case, updates to search indexes – faster. Since we cannot run a MapReduce job over our entire data set every millisecond, we encounter competing needs; the need to process all data holistically conflicts with the need to quickly apply incremental updates to that processing.

This difference may seem simple, but has deep implications. For instance:

-

With MapReduce we can move our computation to the data, but fast updates require moving data to computation.

-

MapReduce jobs produce output as a pure function of the input; realtime processing needs to handle outdated state. For instance, we build a phone book and a name changes from Smith to Jones, realtime processing must remove the outdated entry, whereas MapReduce simply rebuilds the whole phone book.

-

MapReduce jobs often assume a static set of complete data, whereas realtime processing may see partial data or new data introduce in an unexpected order.

And despite these differences, our processing output must be the identical; we need to apply the same logic across very different processing models.

Realtime and batch layers

These significant differences mean different processing infrastructures. Nathan Marz described this well in his How to Beat the CAP Theorem post. The result is a system that uses complementary technologies: stream-based processing with Storm and batch processing with Hadoop.

Interestingly, HBase sits at a juncture between realtime and batch processing models. It offers aspects of batch processing; computation can be moved to the data via direct MapReduce support. It also supports realtime patterns with random access and fast

reads and writes. So our realtime and batch layers can be viewed like this:

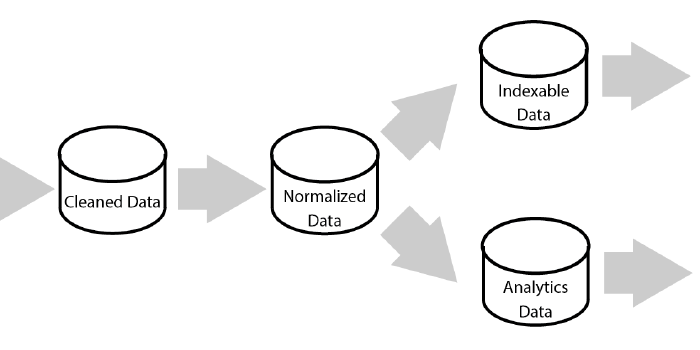

- Data entering the system is persisted in HBase.

- MapReduce jobs are used to create artifacts useful to consumers at scale.

- Incremental updates are handled in realtime by processing updates to HBase in a Storm cluster, and are applied to the artifacts produced by MapReduce jobs.

Processing HBase updates in realtime

So new data lands in HBase but how does Storm know to process it? There is precedent here. Google’s Percolator paper describes a technique for doing so over BigTable: it writes a notification entry to a column family whenever a row changes. Processing components scan for notifications and process them as they enter the system.

This is the general approach we have taken to initiate processing in Storm. Google’s Percolator strategy does not translate directly to HBase. Differences in the way regions are managed versus BigTable tables made using a different column family impractical. So we use a separate “notification” table to track changes to the original. Updates to HBase go through an API that writes notification entries as well as the data itself. We then wrote a specialized Storm spout that scans the notification table to initiate processing of updates.

The result is processing infrastructure like this, with Storm Spouts and bolts complementing conventional MapReduce processing:

The processed data model may be another set of HBase tables, a relational database, or some other data store. Its design should be centered on the needs of the applications and services, letting the processing infrastructure build data for those needs. It is important to note that MapReduce output should be done with a bulk load operation in order to avoid saturating the processed data store with individual updates.

This basic model turns out to be robust. Volume spikes from source systems can be spread throughout the HBase cluster. There are a couple key steps for success here:

-

Regular major compactions on the notification HBase tables are essential. Without major compactions, completed notifications will pile up and performance of the system will gradually degrade.

-

The notification tables themselves may be small in size, but should be aggressively split across the cluster. This spreads load to handle volume spikes and improve concurrency.

Also note that MapReduce is still an important part of the system. It’s simply a better tool for batch operations like bringing a new data set online or re-processing an existing data set with new logic.

Measure Everything

There are a number of moving parts in this system, and good measurements are the best way to ensure it’s working well. For example, in development we found our HBase Region Servers would encounter frequent but short-lived process queues during heavy load. This didn’t look like an issue in HBase, but when we measured the performance of the calling process there was a noticeable degradation. The point is, instrumentation built into Hadoop and HBase are great but not sufficient. Measuring the observed performance at all layers is important to create an optimal system.

There are many good technologies for doing so. We generally use the Metrics API by Coda Hale. Here is an example of HBase client throughput using an instrumented implementation of HTableInterface. The data is collected by the Metrics API and displayed with Graphite:

Different models, same logic

The same logic needs to be applied to both batch and stream processing despite the necessary differences in infrastructure. This is a challenge since the models speak very different languages: InputFormats describe an immutable and complete set of data, whereas event streams expose incremental changes without context.

It turns out the function is the only real commonality between them; simply taking a subset of input and returning useful output. So, our strategy is this:

Build all logic as a set of simple functions, then compose and coordinate those functions with higher-level processing libraries.

We use Storm to compose our realtime processing and Apache Crunch to compose our MapReduce jobs. Here are some lessons we have learned to apply this strategy effectively:

Minimize intermediate state

Persisting intermediate state can be expensive and creates complex relationships between moving parts. This is particularly true if a MapReduce job creates intermediate state used by realtime processing or vice versa. Instead, keep processing pipelines independent whenever possible and combine the results at the end.

Isolate processing models

Our MapReduce jobs are typically run on separate infrastructure than realtime processing to ensure expensive jobs do not saturate time-critical processing.

Be aware of the semantic differences in the processing models

A “join” in a MapReduce job sees all data, whereas a “join” in stream processing gets incremental subsets. If a function needs the full context to execute, that context must be externally loaded in the realtime processing system. In our case, external state is loaded from HBase and cached, but projects like Trident are now providing some aggregation facilities over storm as well.

The path forward

The patterns here have been successful but require significant scaffolding and infrastructure to bring together. Near-realtime processing demands over big data are bound to increase, which means there is an opportunity here; higher level abstractions should emerge. Similar to how tools like Crunch and Hive offer abstractions over MapReduce, it’s likely that similar primitives can express the patterns described here.

How these higher abstractions emerge remains to be seen, but there is one thing I’m sure of: it’s going to be fun.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to acknowledge key contributors to building this and related systems: Jason Bray, Ben Brown, Robert Farr, Preston Koprivica, Swarnim Kulkarni, Kyle McGovern, Andrew Olson, Mike Richards, Micah Whitacre, Greg Whitsitt, and others.