The Plain Text is a Lie

There is no such thing as plain text

“But I see .txt files all the time” you say. “My source code is plain text” you claim. “What about web pages?!” you frantically ask. True, each of those things is comprised of text. The plain part is the problem. Plain denotes default or normal. There is no such thing. Computers store and transmit data in a number of methods; each are anything but plain. If you write software, design websites or test systems where even a single character of text is accepted as input, displayed as output, transmitted to another system or stored for later - please read on to learn why the plain text is a lie!

The topic of text handling applies to many disciplines:

- UX/web designers - Your UX is the last mile of displaying text to users.

- API developers - Your APIs should tell your consumers what languages, encodings and character sets your service supports.

- DBAs - You should know what kinds of text your database can handle.

- App developers - You apps should not crash when non-English characters are encountered.

After reading this article you will …

This topic has been extensively written about already. I highly recommend reading Joel Spolsky’s The Absolute Minimum Every Software Developer Absolutely, Positively Must Know About Unicode and Character Sets (No Excuses!). You should also read up on how your system handles strings. Then, go read how the APIs you talk to send/receive strings. Pythonistas, check out Ned Batchelder’s Pragmatic Unicode presentation.

OK, let’s get started!

Part I - Gallery of FAIL or “When text goes wrong, by audience” thumbnail: “resume.jpeg”

Let’s start off by demonstrating how text handling can fail, and fail hard. The following screen shots and snippets show some of the ways text handling can fail and who should care about the type of failure.

UX and web people

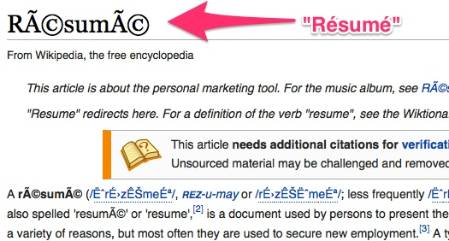

The above image shows the English wikipedia article on Résumés with garbled text. Garbled text can happen if your web pages don’t specify an encoding or character set in your markup. Specifying the wrong encoding can also cause garbled text. XML and JavaScript need correct character sets too. It’s important to note that no error or exception was raised here. The text looks wrong to the user, but the failure happens silently.

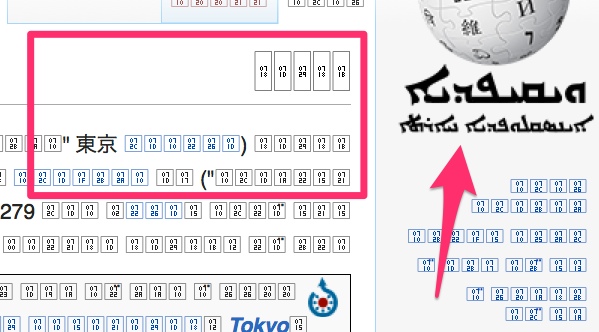

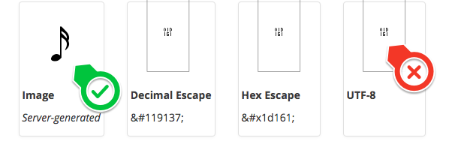

This article on Tokyo above is displayed in a language (Aramaic) that my fonts don’t support. Instead of a symbol, we see a box with a number identifying the un-showable character. If you think that example is too contrived, here is a more commonly used symbol: a 16th note from sheet music. Many perfectly valid characters are not supported by widely used fonts. Specialized web fonts might not support the characters you need.

API developers

//Fetch the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Arabic

documentAPIClient.getTitle(docID=123)

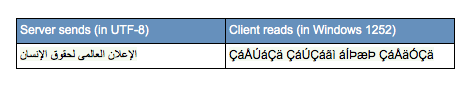

The result of this API call (example source) is similar to the last two examples: nonsense text. This can happen if the client and server use different text encodings. By the way, this situation happens so often that there’s a term for it: Mojibake.

Here are some client/server scenarios resulting in Mojibake:

- The server didn’t document their encoding and the client guessed the wrong encoding.

- The server or client inherit the encoding of their execution environment (virtual machine, OS, parent process, etc.), but the execution environment’s settings changed from their original values.

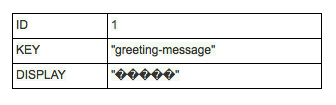

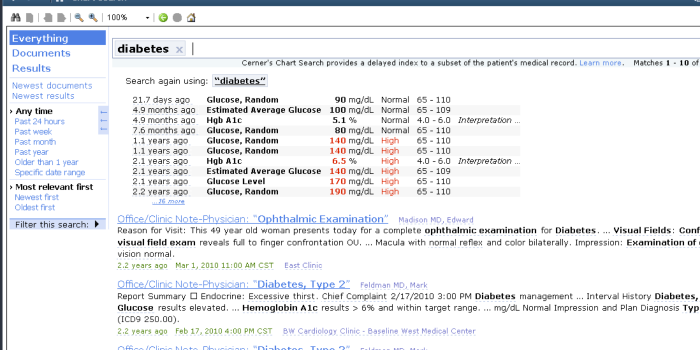

DBAs

Database systems can be misconfigured such that characters sent to the database are not stored accurately. In this example, the offending characters are replaced with the imaginatively-named Replacement Character (“�”). The original characters are forever lost. Worse still, replacement characters will be returned by your queries and ultimately shown to your users. Sometimes, offending characters will be omitted from the stored value or replaced with a nearest match supported character. In both scenarios the database has mangled the original data.

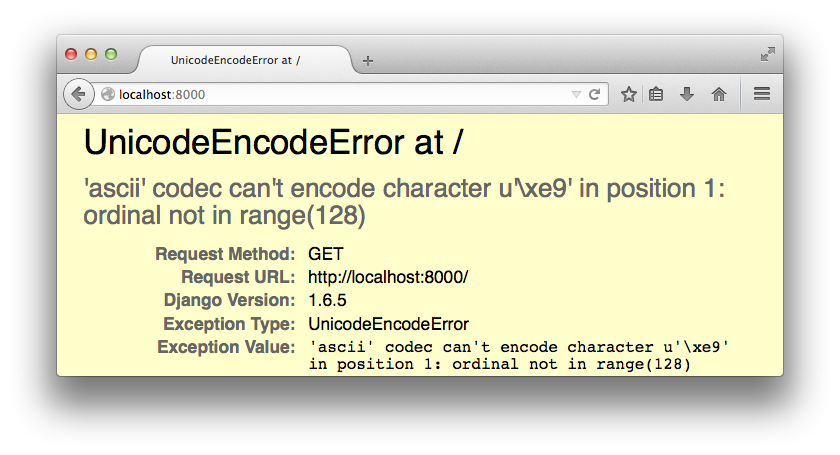

App developers

org.scalatest.exceptions.TestFailedException: "d[é]funt" did not equal "d[é]funt"

at org.scalatest.MatchersHelper$.newTestFailedException(MatchersHelper.scala:160)

...

at sun.reflect.NativeMethodAccessorImpl.invoke(NativeMethodAccessorImpl.java:39)

at com.intellij.rt.execution.application.AppMain.main(AppMain.java:134)

The top image shows the 500 page of an app that crashed when improperly encoding. In the Scala error message (bottom), a property file was read in ISO-8859-1 encoding but had UTF-8 encoded bytes in it. This caused the unit test to fail.

Your source code, web pages, properties files, and any other text artifact you work with has an encoding. Every tool in your development tool chain (local server, terminal, editor, browser, CI system, etc.) is a potential failure point if these encodings are not honoroed.

Part II - Avoid text handling problems

Ghost in the machine

You’ve seen examples of failure and (hopefully) are wondering how such failures can be avoided. To avoid failure you must ask yourself one question: “Can my system store and transmit a ghost?”

GHOST (code point U+1F47B) is a valid (albeit weird) part of the Unicode standard. Unicode is a system of storing and manipulating text that supports thousands of languages. Using Unicode properly will go a long way to prevent text handling problems. Thus, if your system can store, transmit, read and write GHOST then you’re doing it right. But how to handle this GHOST?

Some Terminology

You need to know some terms before the rest of this article will make any sense.

Remembering the difference between encode and decode can be difficult. One trick to keep them straight is to think of Unicode objects as the ideal state of being (thanks, Joel Spolksy) and byte-strings as strange, cryptic sequences. Encoding turns the ideal into a bunch of cryptic bytes, while decoding un-weirds a bunch of bytes back into the ideal state; something we can reason about. Some systems use different terms but the ideas still apply. For example: Java Strings are Unicode objects and you can encode/decode to/from byte-strings with them.

Now that you’ve got the necessary terminology under your belt, let’s prevent text handling problems in our system by making a sandwich; a Unicode sandwich!

Make a Unicode sandwich

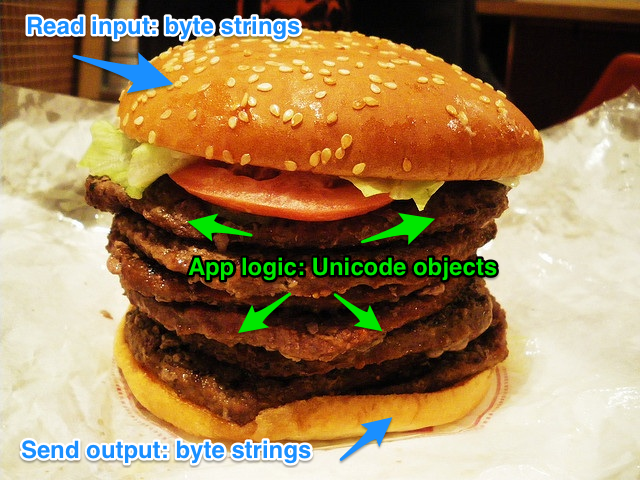

Analogy credit: Ned Batchelder coined the Unicode sandwich analogy in his Pragmatic Unicode presentation at PyCon 2012 (video). It’s so clever that I can’t resist re-using it in this article!

Original imageIn this analogy the pieces of bread on the top and bottom are regions of your code where you deal with byte-strings. The meat in the middle is where your system deals in Unicode objects. The top bread is input into your system such as database query results, file reads or HTTP responses. The bottom bread is output from your system such as writing files or sending HTTP responses. The meat is your business logic.

Good sandwiches are meaty

Your goal is to keep the bread thin and the meat thick. You can achieve this by decoding from byte-strings to Unicode objects as early as you can; perhaps immediately after arrival from another system. Similarly, you should do your encoding from Unicode objects into byte-strings at the last possible moment, such as right before transmitting text to another system.

Working with Unicode inside your system gives you a common ground of text handling that will largely avoid the errors we’ve seen at the top of this article. If you don’t deal in Unicode inside your system then you are limiting the languages you support at best and exposing yourself to text handling bugs at worst!

The best sandwich bread is UTF-8

Your system ultimately needs to send and receive byte-strings at some point, so you must choose an encoding for your byte-strings. Encodings are not created equal! Some encodings only support one language. Some support only similar languages (for example, German and French but not Arabic). Never assume your system will only encounter languages you speak or write! Ideally you will choose encodings that support a great many languages.

UTF-8 is the best general purpose encoding for your byte-strings. You’ll learn why UTF-8 is an excellent encoding choice later in this article in the Unicode: One standard to rule them all section. For now I recommend you:

- Choose UTF-8 for all byte-strings.

- Configure your system to use this encoding explicitly. Do not rely on the parent system (OS, VM, etc.) to provide an encoding since system settings might change over time.

- Document your encoding choice in both public facing and internal documentation.

The UTF-8 encoding supports all the text you’d ever want. Yet, in this imperfect world you might be forced to use a more limited encoding such as ISO-8859-1 or Windows-1252 when interfacing with other systems. Working with a limited encoding presents problems when decoding to and encoding from Unicode: not every encoding supports the full Unicode range of characters. You must test how your system converts between your byte-strings and Unicode objects. In other words, test between the meat and the bread.

Testing between the meat and the bread

The critical areas to test are where bytes strings are decoded to Unicode objects and where Unicode objects are encoded into byte-strings. If you’ve followed the advice of this article thus far then the rest of your app logic should operate exclusively in Unicode objects. Here is a handy table of how to test regions of your system that encode and decode:

Unicode sandwich applies to new projects and legacy systems

Using UTF-8 for I/O, Unicode inside and testing the in-between points will save you from pain and bugs. If you’re building a new system then you have the opportunity to design it with Unicode in mind. If you have an existing system, it is worth your time to audit how your system handles text.

With the practical stuff out of the way, let’s dive deeper into computers and text!

Part III - Encodings, Unicode and how computers handle text

We’ve talked about how you should use Unicode, encodings and byte-strings in your system to handle text. You may be wondering why text handling is so painful at times. Why are there so many encodings and why don’t they all work together in harmony? I’ll attempt to explain a bit of history behind text handling in computers. Understanding this history should shed some light on why text handling can be so painful.

To make things interesting, let’s pretend we are inventing how computers will handle text. Also assume we live in the United States and speak only English. That’s a pretty ignorant assumption for real world software development, but it simplifies our process.

ASCII: Works great (if you want to ignore most of the world)

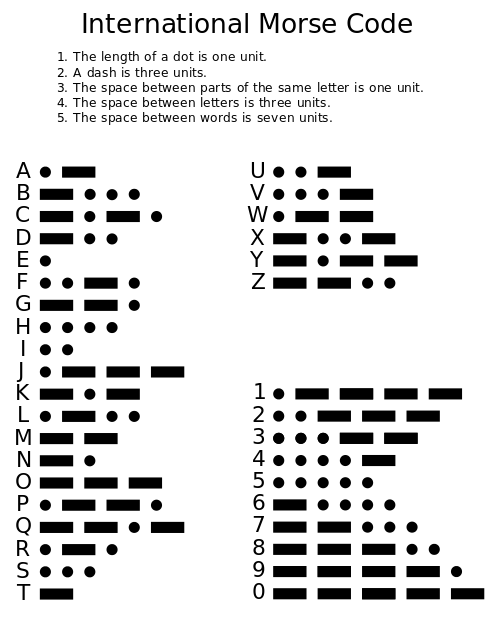

Our challenge is to invent how computers handle text. Morse code is an encoding that pre-dates digital computers but provides a model for our approach: Each character has a transmission sequence of dots and dashes to represent it. We’ll need to make a few changes and additions though…

Image sourceRather than dots and dashes we can use 1’s and 0’s (binary). Let’s also use a consistent number of bits per character so that it’s easy to know when one character ends and another begins. To support US English we need to map a binary sequence to each of the following:

- a-z

- A-Z

- 0-9

- " “(space)

- !”#$%&’()*+,-./:;<=>?@[\]^_`{|}~

- Control characters like “ring a bell”, “make a new line”, etc.

That’s 96 printable characters and some control characters for a total of 128 characters. 128 is 27, so we can send these characters in seven-bit sequences. Since computers use eight-bit bytes, let’s decide to send eight bits per character but ignore the last bit. We have just invented the ASCII encoding!

ASCII forms the root influence of many text encodings still used today. In fact, at one time ASCII was the law: U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson mandated that all computers purchased by the United States federal government support ASCII in 1968.

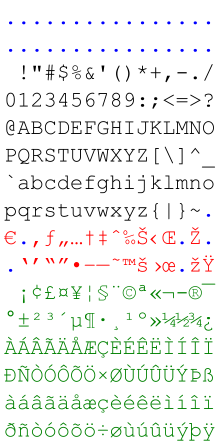

Image sourceInternational and OEM standards: Supporting other languages

Starting with similar languages to US English

We need more space to pack in more symbols if we want to support other languages and other symbols like currencies. It seems reasonable that people typically deal with a block of languages that are geographically or politically related, and when we’re lucky those languages share many of the same symbols. Given that assumption we can create several standards; each one for a block of languages!

For each block, we can keep the first 128 characters as-is from ASCII (identical bit sequences) so that the US English characters and Arabic numerals are still supported. We can then use the eighth bit for data instead of ignoring it. That would give us eight bits per character and a total of 256 characters to work with (double ASCII’s paltry 128). Now let’s apply that eight bit.

A bunch of countries in Western Europe use the same latin alphabet plus special diacritics (also known as accent marks) like ü or é or ß. In fact, we can pack enough extra characters in those last 128 slots to support 29 other languages like Afrikaans, German, Swahili and Icelandic. Our Western European language block encoding is ready! We call this type of encoding a single-byte encoding because every character is represented by exactly one byte.

Image sourceAdditional single byte encodings for other language blocks

We can repeat the same process we used to create our Western European language encoding to develop other single-byte encodings for other language blocks; each a 256 character set! To give one more example, let’s build a single byte coding for Arabic.

Again, we take the first 128 ASCII characters as-is, then fill up the last 128 with the Arabic alphabet We’ve got some space left over. Arabic has some diacritics as well, so let’s use some of the leftover slots to hold diacritic marks that are only valid when combined with other letters.

Some languages don’t even fit in 256 characters. Chinese, Japanese and Korean for example. That’s OK, we’ll just use multiple bytes per character to get more room. As you may have guessed, these encodings are called multibyte encodings. Sometimes we choose to use the same number of bytes for every character (fixed width multibyte encodings) and sometimes we might choose to use different byte lengths (variable width multibyte encodings) to save space.

Ratifying our encodings to standards

After we’ve built several of these encodings (Russian, Greek, Simplified Chinese, etc.) we can ratify them as international standards such as ISO-8859 for single byte encodings. We previously built ISO-8895-1 (Western European) and ISO-8859-6 (Latin/Arabic). International standards for multibyte encodings exist too. People who use the same standard can communicate without problems.

The international standards like ISO-8895 are only part of the story. Companies like Microsoft and IBM created their own standards (so-called OEM standards or code pages). Some OEM standards map to international standards, some almost-but-not-quite map (see Windows-1252) and some are completely different.

Our standards have problems

Our standards and code pages are better than ASCII but there are a number of problems remaining:

- How do we intermix different languages in the same document?

- What if our standards run out of room for new symbols?

- There is no rosetta stone to allow communication between systems that use different encodings.

Enter Unicode.

Unicode: One standard to rule them all

Image sourceAs mentioned earlier, Unicode is a single standard supporting thousands of languages. Unicode addresses the limitations of byte encodings by operating at a higher level than simple byte representations of characters. The foundation of Unicode is an über list of symbols chosen by a multinational committee.

Unicode keeps a gigantic numbered list of all the symbols of all the supported languages. The items in this list are called code points and are not concerned with bytes, how computers represent them, or what they look like on screen. They’re just numbered items, like:

a LATIN SMALL LETTER A - U+0061

東 Pinyin: dōng, Chaizi: shi,ba,ri - U+6771

☃ SNOWMAN - U+2603

We have virtually unlimited space to work with. The Unicode standards supports a maximum of 1,114,112 items. That is more than enough to express the world’s active written languages, some historical languages and miscellaneous symbols. Some of the slots are even undefined and left to the user to decide what they mean. These spaces have been used for wacky things like Klingon and Elvish.

Fun fact: Apple Inc. uses U+F8FF in the Private Use Area of Unicode for their logo symbol (). If you don’t see the Apple logo in parenthesis in the preceding sentence, then your system doesn’t agree with Apple’s use of U+F8FF.

OK, we have our gigantic list of code points. All we need to do is devise an encoding scheme to encode unicode objects (which now we know are lists of code points) into byte-strings for transmission over the wire to other systems.

UTF-8

UTF-8 encodes every Unicode code point in between one and four byte sequences. Here are some cool features of UTF-8:

- Popularity - It’s the dominant encoding of the world wide web since 2010.

- Simplicity - No need to transmit byte order information or worry about endianness in transmissions.

- Backwards compatibility - The first 128 byte sequences are identical to ASCII.

UCS-2: Old and busted

UCS-2 is a fixed width, two-byte encoding. In the mid-nineties, Unicode added code points that cannot be expressed in the two-byte system. Thus, UCS-2 is deprecated in favor of UTF-16.

- UCS-2 was the original Java String class’s internal representation

- C Python 2 and 3 use UCS-2 if compiled with default options

- Microsoft Windows OS API used UCS-2 prior to Windows 2000

UTF-16: UCS-2++

UTF-16 extends UCS-2 by adding support for the code points that can’t be expressed in a two-byte system. You can find UTF-16 in:

- Windows 2000 and later’s OS API

- The Java String class

- .NET environment

- OS X and iOS’s NSString type

UTF-32: Large bytes, simple representation

UTF-32 is a simple 1:1 mapping of code points to four-byte values. C Python uses UTF-32 for internal representation of Unicode if compiled with a certain flag.

Conclusion

We’ve seen how text handling can go wrong. We’ve learned how to design and test our systems with Unicode in mind. Finally, we’ve learned a bit of history of text encodings. There is a lot more to the topic of text, but for now I ask you do to the following:

- Examine your system to see if you’re using Unicode inside

- Use UTF-8 when reading and writing data

- Know that the plain text is a lie!

Thanks for reading!